5. Roadmap#

Solutions for Leveraging Private Investment to Support Forest Health and Watershed Restoration.

5.1. Takeaways#

Key takeaways include the following:

Blended funding. A blend of public and private funding is needed to accomplish the projects identified in the region at the scale and pace that best responds to emerging risks and opportunities.

Payors willing to invest in projects based on the value of avoided costs continue to challenge conservation finance development.

Ecosystem services. Creating opportunities to complement state and federal funding sources with revenue from payments for the benefits of restoration, forest health management, or mitigation projects, such as the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol, could greatly increase the scale and impact of restoration projects in the region.

Centralized administration. A centralized entity could be critical in managing public grants, contracts, environmental compliance, and private funds. Several Feedstock Aggregation pilot projects in Northern California are developing joint powers authorities to consolidate feedstock from forest health projects to increase the utilization and use of forest products.

5.2. Background#

This Roadmap is intended to provide solutions to the many challenges facing conservation finance. The Burney-Hat Creek Collaborative (see pulldown) started the development of its ideas.

Burney-Hat Creek Collaborative

In recent decades, local northeast California communities have experienced high rates of unemployment and increased risks of high-severity wildfires, issues the Collaborative actively works to mitigate. The Burney Hat Creek Community Forest and Watershed Group (BHC), founded in 2009, is a collaborative forestry effort dedicated to improving social, environmental, and economic conditions in the Burney Creek and Hat Creek watersheds. The Collaborative footprint encompasses 364,250 acres of public, private, and Tribal lands and the communities of Burney, Johnson Park, Hat Creek, Cassel, and Old Station.

The group’s vision is to create a fire-resilient forest ecosystem with sustainable populations of wildlife, fisheries, and habitat, functioning and restored watersheds and water quality, protected cultural resources, and appropriate recreational opportunities while also helping to support quality of life, jobs for diverse community members, and economic benefits in local communities. Post-fire recovery following large wildfires, such as the 2021 Dixie Fire, shows the challenges of protecting forests, water supplies, and communities and the need for increased investment to reduce fire risk and create healthier, more resilient forests and watersheds.

The Fall River Resource Conservation District, working with grant funding from the California Governor’s Office of Land Use & Climate Innovation (formerly known as the Office of Planning and Research or OPR), initiated a Pilot Project known as the California Forest Residual Aggregation and Market Enhancement (CalFRAME) Pilot Project to aggregate feedstock so that existing and emerging businesses can secure long-term contracts for forest wood products. Numerous small and industrial businesses are working to sustainably manage California forests in this geography’s Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) and wildlands. The project’s main goal (and challenge) is developing and sustainably funding a joint powers authority to manage feedstock aggregation in the region.

The region faces similar challenges to those of other rural forested regions in California: difficulty in sustainable funding, workforce availability and capacity, and transportation. Workforce development and transportation are beyond the scope of this publication, although some funding could help with each of these two challenges. Let’s shift to funding categories that are possible for similar communities.

5.3. Funding#

Funding is a partial solution to several barriers to implementing forest restoration projects. However, rather than focusing on individual funding sources and types, developing strong financial mechanisms that collate a portfolio of funding for any project, program, or landscape may be a higher priority. We have organized this section to be brief and organized to focus on non-traditional and less well-established topics. More traditional funding sources can be found in the dropdown below. The Roadmap is not meant to be a definitive funding guide source; we describe funding and investment resources, including the grant roster developed by project proponents, that may be considered, along with descriptions of non-tradition funding sources.

5.3.1. Traditional Funding#

Traditional funding, such as grants, can support any collaborative finance project. Government grants are frequently and readily available, although they can be difficult to secure given the competition for funds. Nevertheless, public funding can provide a way to pilot or test new ideas while reinforcing proven programs and technologies. Examples are provided in the dropdown below.

Traditional Funding Sources

Grants

State and federal agency grants have been the bulwark of funding in California, especially with forest health projects. Although grant funding cycles up and down with state budget surpluses and deficits, overreliance on grants can be problematic for many organizations. Nearly all agency grants are reimbursable; e.g., you must spend the funds and request reimbursement. This places an undue burden on small organizations that do not have a line of credit or ample surplus in their bank accounts.

Loans

Public, private, and nonprofit entities often use loans to cover the initial costs of projects, payroll, or material costs when awaiting reimbursement from state and federal grants or investing in or augmenting a business. The pluses of loans are availability, rapid deployment, and low interest rates. The minuses are debt servicing, the ability to pay back when returns are low, do not exist or are not possible for certain projects, and inaccessibility for entities without an established track record. Loan programs that can be subsidized and managed by public agencies (e.g., GoBiz) have a role in easing access to capital for equipment and infrastructure purchases. A zero- to low-interest loan program could be instrumental in delivering forestry and wood products utilization machinery to forested communities.

Corporate

Corporate contributions to environmental sustainability are increasing in response to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, increased corporate responsibility focus, and links to dependence on natural resources. Funding from corporations can often be a long haul, is heavily dependent on connections within corporate sustainability offices or executive suite officers, and may not be similar in size to grants to foundations and public funding sources. However, corporations often offer additional resources in addition to funding. Patagonia, for instance, offers modest grants of approximately $30,000 but also gives access to their communications and media departments to grantees. Corporations are highly interested in payments for ecosystem services and quantifiable outcomes. The parametric insurance example mentioned below is where corporate entities have been involved in funding restoration projects that also protect business assets and may offer avoided cost savings or a return on investment.

Philanthropic

Philanthropic foundations can play key roles in developing conservation finance strategies for forest and watershed restoration by providing grants or other investments in the projects or organizations that undertake them. Foundations can operate at regional and national levels; there is considerable interest in supporting projects that increase climate resilience, boost workforce and economic development, and sustain rural communities across these sectors. Foundation support may come in grants to cover operating expenses and project development activities. Some foundations also provide investments, known as Program Related Investments (PRIs) or Mission Related Investments (MRIs), for which they generally expect a below-market rate or nominal interest return.

Taxes/fees

Taxes, measures, and fees can effectively raise consistent revenue over longer periods. In 2020, for example, Marin County approved Measure C to fund wildfire prevention and preparedness efforts. The resulting 10-year parcel tax levies $0.10/building ft2, providing nearly $20 mn/yr to prevent and mitigate wildfires in Marin County managed through the Marin Wildfire Prevention Authority Joint Powers Agreement. Raising taxes can be challenging for rural communities without a strong commercial and private housing real estate market. California law requires voter approval of new or increased taxes. However, when tied to re-investment in the community, tax proponents may succeed in making a case for a temporary assessment.

5.3.2. Collaborative Finance#

Blended financing strategies that assemble a diverse portfolio of funds from public grants and add private resources can be key to creating a locally appropriate and collaborative finance portfolio. We believe these strategies may support forest and watershed restoration projects undertaken by BHC and economic or community development efforts that can support those restoration projects.

Collaborative finance is a conservation finance strategy that involves cooperative interaction between individual project developers, stakeholders, and finance providers. This process may or may not include traditional financial institutions (collaborativefinance.org). We broaden the term to include finance developed by fair and equitable participation of stakeholders in a region, landscape, or watershed to address natural resource and infrastructure management needs, utilizing multiple forms of funding from public grants to private investment. Finance approaches may include outcomes-based finance models such as environmental impact bonds. For a deeper discussion of collaborative finance approaches to financing water infrastructure in California, see [Odefey and Russell, 2020].

Collaborative Finance Funding Sources

Payments for Ecosystem Services

State and federal grants for conservation, wildfire mitigation, and restoration are indirect payments from the public for ecosystem services and biodiversity conservation. In any region, however, the public’s willingness to pay for additional benefits may often be voluntary, e.g., a GoFundMe campaign or a specialized nonprofit that funds and works to protect a local trail system, a charismatic local species, or a historical monument. However, more organized campaigns may be structured or codified into local or regional policies based on voluntary contributions (e.g., dollar check-off programs). These are often successful in areas that have tourism without entrance fees. One example is the National Forest Foundation’s Ski Conservation and Forest Stewardship Fund. Funds come from voluntary guest contributions at ski areas or lodges operating on National Forest System Lands. They must go to restoration projects in the forest where the ski area is located. An opt-out approach works best in these scenarios, e.g., a contributor must uncheck a box to indicate they do not want to contribute.

Larger watershed contribution programs throughout the West combine public and private funds to protect water resources and fund restoration or fire mitigation projects. Typically, these funds are more successful when close to larger urban areas, such as the Salt River Project and the Northern Arizona Forest Fund. A similar approach could be taken in the Burney-Hat Creek through a regional fund that adds $1 to room nights in all hotels, Airbnb rentals, and outdoor recreation businesses. Another approach would be to connect hunters and anglers who regularly visit the region and are interested in restoring forest, riparian, and other associated habitats.

Environmental Impact Bonds

One outcome of a collaborative finance strategy may be the development of an environmental impact bond. In 2017, Quantified Ventures and the District of Columbia’s Department of Water and Sewer (DC Water) launched the nation’s first environmental impact bond focused on implementing green infrastructure to reduce sewage overflows and flooding (Martin and Appelbaum, 2021). This outcomes-based investment package tied the rate investors earned to achieving specified environmental performance goals. The investment package structure linked DC Water to private bond buyers. The structure used by Quantified Ventures, DC Water, and their investors follows the track illustrated below. The role of the third-party evaluator is noteworthy in this outcomes-based repayment scheme. Five years after launching the project, the evaluator confirmed that stormwater runoff had been reduced by nearly 20%, a level that met the Bond’s base-level repayment criteria (Lindsay et al., 2021).

Blue Forest Conservation’s Forest Resilience Bond adopts a different approach. The Bond, more of a revolving loan instrument, is not, strictly speaking, an outcomes-based financing strategy. The project payor, Yuba Water Agency, makes payments to investors unrelated to achieving the project’s many benefits. The structure adopted by Blue Forest enables the creation of a portfolio of investors and funders who repay and complement the agency’s funding.

EIFDs

Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts (EIFDs) are a recent evolution of the tax increment financing tools previously developed in California and support financing infrastructure projects with anticipated increased property tax revenues associated with the future benefits of the projects (Lefcoe, 2014). Revenues from Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts can be used for public works, transportation, parks, libraries, and water and sewer facilities, emphasizing sustainable community goals under California’s landmark climate legislation (Flint, 2018). Recent revisions to the Enhanced Infrastructure Financing District law reduced some of the challenges to adoption; for example, no public vote is required to establish a District. In 2017, the City of West Sacramento created a new Enhanced Infrastructure Financing District, which is expected to raise $1.1 billion for parks, stormwater, sewage, and other infrastructure improvements. While a more appropriate vehicle for cities and urban populations due to the housing density, it is possible that broad landscape-scape districts could be adapted to more rural areas.

Revolving Loan Funds

Pooled funding sources such as impact bonds or revolving loan funds can help end the project->project funding cycle with greater funding available and at larger scales. Typically offered at lower than market interest rates, revolving loan funds are self-replenishing pools of money utilizing principal and interest payments on existing loans to issue new loans. They have been used effectively on small to large scale to develop businesses, assist healthcare, and improve environmental outcomes. They are flexible, can be used with more conventional funds such as grants and loans, and have been used for decades in developing and developed countries.

For example, through a coalition of public and private partners, the Wildfire Mitigation Environmental Impact Fund intends to utilize resources from private investors and revenues from biomass generated from forest thinning to offset the financial burden for wildfire mitigation in the San Juan National Forest wildland-urban interface. The project fosters regional collaboration through shared project financing and implementation. It also creates the opportunity for scaling up forest treatments and fire reduction by creating a revolving loan fund that reinvests proceeds into additional projects, ensuring that capital is available for long-term re-treatment and expansion of forest health interventions.

Because of its revolving loan nature, the impact of the fund will continue to grow over time as capital is redeployed for forest health treatments in new areas beyond this initial plan. The Environmental Impact Fund will deploy financing for an initial proposed plan to reduce wildfire risk over 64,871 acres in Southwest Colorado, encompassing private, federal, state, local, and tribal lands. An analysis of three representative parcels within the larger proposed geography demonstrated a benefit-cost ratio of nearly 300% based on avoided risk and damage to properties, infrastructure, and water resources if a wildfire were to occur. In addition, an estimated 287,708 green tons of biomass would be made available through the treatments, which can be converted to electricity or other commercial uses if biomass plants can be built to consume the woody by-products of forest restoration projects.

Avoided Wildfire Emissions

Spatial Informatics Group and Element Markets are developing a forecast methodology under the Climate Forward program to recognize the climate benefits associated with fuel treatment activities that lower the risk of catastrophic forest fires and their emissions—known as the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Forecast Methodology, the final product is expected by June 2022 and could provide complementary funding for thinning and prescribed fire projects to grants and private investments. The Protocol differs from carbon offsets in that forecasted mitigation units (FMUs) are issued for forecasted greenhouse gas reductions or removals. FMUs are used to mitigate anticipated future emissions, such as wildfires. FMU credits were created today to address future impacts and equal one metric ton of CO2e. Thomas Buccholz of the Spatial Informatics Group gave the committee an overview of the Protocol on May 17, 2022.

Carbon Markets

Carbon markets offer an opportunity to secure gap or stack funding for on-the-ground forest management activities, such as thinning, pruning, mastication, mechanical treatment, and even prescribed burning. Revenue realized through the carbon market could help the JPA to treat more forest land than otherwise possible and generate additional biomass that could be put under supply contracts to support existing and emerging infrastructure. Market prices for carbon credits vary depending on a given project’s size and location, treatment type, and the carbon market or registry used. Carbon credits can be realized for projects of any size and located on federal, state, and private lands. See the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol section as another approach that is easier to implement than carbon sequestration credits or markets since the avoided costs are already calculated, and proponents do not have to seek an entity to purchase the credits. The downside of carbon markets is the high cost of entry. In places where cap and trade programs exist, such as California, there is no additional incentive to participate in voluntary markets from private sources.

Parametric Insurance

Parametric or index-based insurance covers the probability of a predefined event instead of indemnifying actual loss incurred (Swissre, 2018). These so-called trigger events are typically disaster (e.g., wildfire, flooding, hurricane, earthquake) related and measured through triggers such as wind speed, quake magnitude, or rainfall amount. Insurable triggers must happen by chance and are modeled. When the triggers are reached, a predetermined pay-out is made regardless of the sustained physical losses. Parametric insurance is meant to complement existing indemnity insurance but is increasingly used for post-disaster restoration funding in the natural world. One of the earliest examples of its use for nature recovery is the Mesoamerican Reef parametric insurance that provided $800,000 for reef restoration following Hurricane Delta. The trigger was windspeed with a parameter greater than 100 knots. The funds came from the Coastal Zone Management Trust (Winters, 2020). Using insurance to protect natural areas and their communities may uniquely connect public and private finance at an ecosystem scale.

Climate Catalyst Fund

The California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank, known as IBank, has a Climate Catalyst Revolving Loan Fund designed to jumpstart critical climate solutions through flexible, low-cost credit and credit support, bridge the financing gap that currently prevents these advanced technologies from scaling into the marketplace; mobilize public and private finance for shovel-ready projects that are stuck in the deployment phase; and accelerate the speed and scale at which technologically proven, critical climate solutions are deployed. On the forestry side, the focus has been on forestry practices, wood products, and biomass utilization, focusing on initial projects that can reduce wildfire threats. Financing zero or low-interest loans for biomass infrastructure is a distinct possibility. Recent calls with these entities indicate a high interest for IBank and GoBiz to become more involved in the region, particularly to support finance related to equipment and infrastructure.

Fintech & Blockchain

Technology in the financial realm is already revolutionizing the world of investment. Blockchain technology could help finance projects, connect payors to them, and provide collaborative digital platforms that connect funders to implementers and hasten pace and scale. With rapid iteration from finance to project and a community that governs and builds a permissionless system through open, collaborative, and equity-based protocols, the forest restoration blockchain system could rapidly evolve if the technology can be deployed, tested, and widely adopted. In other words, this is an unproven resource but rapidly changing and worth watching. It has mostly been applied to reforestation and carbon sequestration projects. Let’s look at how it might work.

The Open Forest Protocol has a five-step approach for reforestation (Kelly, 2022):

Forested land plots are registered using an online protocol.

Remote sensing and ground-truthed data are gathered, recorded, and analyzed in an online map portal. Spatial and monitoring project data is stored permanently in an open distributed blockchain ledger, a shared database spread across multiple sites, regions, or participants.

Independent validators use remote-sensed data, ground surveys/monitoring, or drones to ensure data legitimacy.

Forestation projects gain transparency and trust through monitoring and validation.

Operators have access to carbon, reforestation, and restoration financing when projects meet outcomes and are successful.

Blockchain can be utilized further through smart contracts, an automated contract that executes when specified events, actions, deliverables, or other terms are met. Some of these concepts are applied to planning and permitting in a centralized one-stop shop, but that is outside the scope of this roadmap.

How does this work for funding, however? Let’s examine a hypothetical case based on platforms we know are being developed. In this case, the following steps are taken for listing a project that will create carbon credits:

A project implementer designs a project that a neutral third party or agency vets. The project proponent can access the listing engine and generate a project file.

A carbon rating company accesses the project file. The company then issues an investment recommendation.

If approved, the project file goes to the investor pool. A limited review period, e.g., 30 days, ensues

After the investor review, a portion of the carbon credits is auctioned among pool investors.

The project is listed on the exchange if the auction clears the reserve price. Successful bidders receive tradable carbon credits, and the project proponents receive upfront funds from a portion of the carbon credits to initiate the project.

Project reporting ensures quality, transparency, and successful projects.

5.4. Collaborative Finance Roadmap#

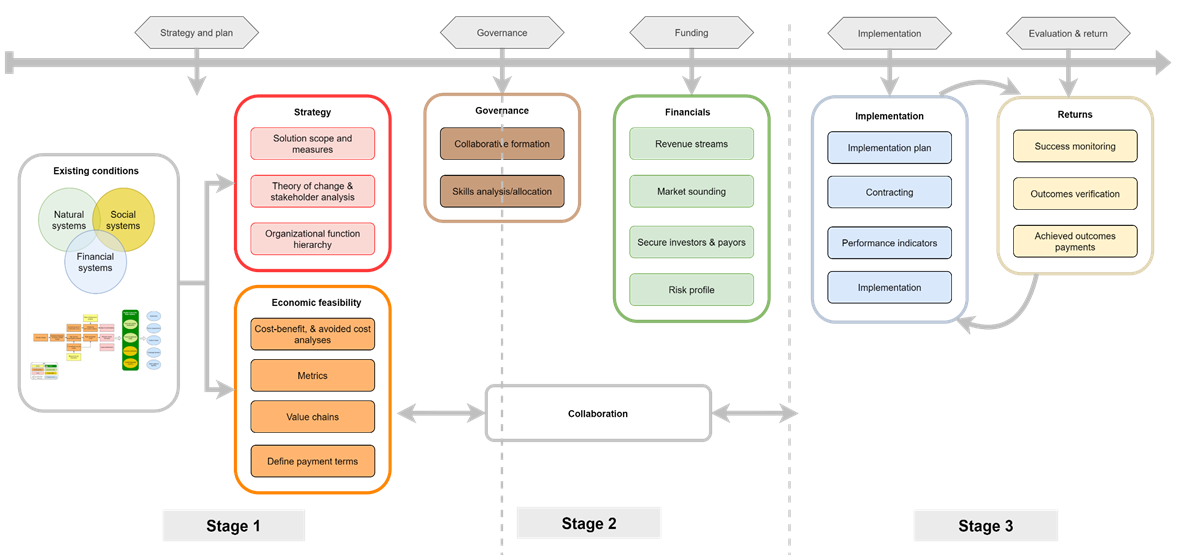

Inspired by the nature-based solutions finance roadmap outlined by Altamirano et al. [2021], we set out to create an adapted version from our experiences promoting these approaches in Northern California ([Russell and Odefey, 2021]). The collaborative finance roadmap shown in Fig. 5.1 outlines steps leading from an initial analysis of existing conditions and creating a strategy to developing a governance structure, securing funding, and implementing the project.

Fig. 5.1 Collaborative finance roadmap.#

The collaborative finance roadmap includes three key stages in its development:

Capitalization. Developing a collaborative finance strategy can start by analyzing existing conditions by considering relevant natural, social, and financial systems. We highly recommend developing a theory of change or situation model that uses a box-and-arrow diagram approach to visually depict how the system works and potential interventions and approaches for improving it, including reducing the barriers to diversifying project finance ([Margoluis and Salafsky, 1998]). The model provides the foundation for developing a theory of change, solution scope, and setting shared goals and measures. It can also inform an analysis of the strengths of each organization involved in the collaborative and their roles in developing the chosen collaborative finance model.

Implementation. Establishing a governance structure is vital for creating a functioning, collaborative environment. In some cases, a single agency may lead projects without any collaboration required. This approach may be less frequent, considering the broad landscape scale and jurisdictional complexities required for many infrastructure and restoration projects. Further development of financial details includes revenue streams, market sounding, securing the investors and payors, and risk profile during Stage 2.

Outcomes. Securing payors is possibly the most critical barrier to overcome for collaborative finance. As a result, this work needs high priority from the collaborative and may need initiation during Stage 1. Federal and state funders can be notoriously slow to issue and sign contracts following grant awards. Following contracting, implementation depends on setting performance indicators and a clear implementation plan that outlines the timeline for project execution and management and project evaluation, success monitoring, verification of outcomes, and return payments.

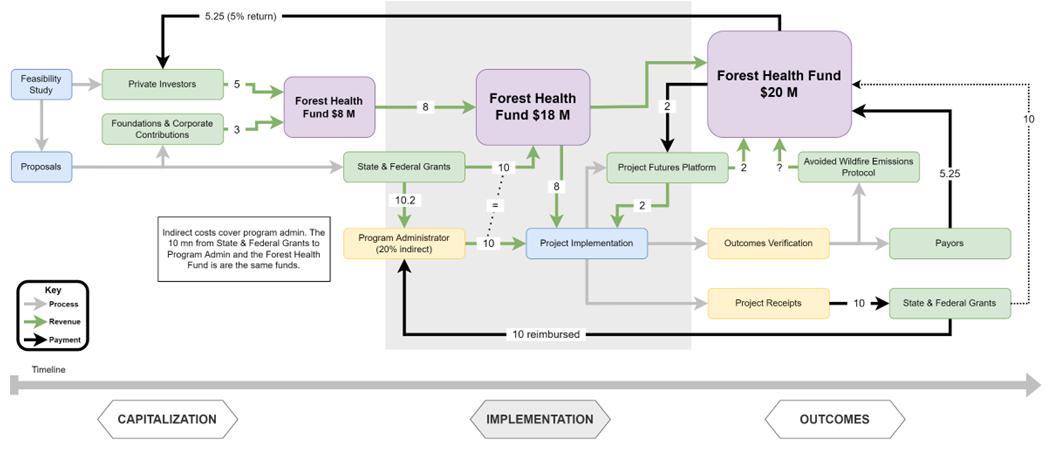

At a more specific local level, the following may be how a collaborative or partnership may leverage private finance funds to create a hypothetical Forest Health Fund (Fig. 5.2):

Collaborative works identify the existing funding situation and solution process, culminating in a feasibility study with predetermined outcome metrics.

Initial funding comes from state and federal grants.

Additional funding comes from private sources.

The portal provides a steady, up-front source of income through auctions of carbon credits or other marketable ecosystem services.

If participating, the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol creates forecasted mitigation units (FMUs) based on each planned project or grouping of projects.

When state grant expenses are reimbursed, the invoiced funds are returned to the fund by the program administrator (minus 20% overhead)

When project outcomes are met and verified, an outcome trigger creates a payment return to investors from the project payors.

Fig. 5.2 Hypothetical Forest Health Fund capitalization and funding over time.#

5.5. Portal#

Connecting local organizations and communities to funders is challenging, especially in rural areas where most forested regions are located. To bridge this gap, we envision creating a conservation finance portal over the long term that mainly helps connect project implementers, investors, and payors (Fig. 5.3). The portal will principally focus on leveraging private funds but could increase attractiveness by centralizing public funding.

Fig. 5.3 Conceptual framework for a conservation finance portal.#

A potential process that conservation finance portal participants might follow to use the conservation finance portal could include the following steps:

A project implementer designs a project that a neutral third party or agency vets. The project proponent can access the listing engine and generate a project file.

A carbon rating company accesses the project file. The company then issues an investment recommendation.

If approved, the project file goes to the investor pool. A limited review period, e.g., 30 days, ensues

After the investor review, a portion of the carbon credits is auctioned among pool investors.

The project is listed on the exchange if the auction clears the reserve price. Successful bidders receive tradable carbon credits, and the project proponents receive upfront funds from a portion of the carbon credits to initiate the project.

Project reporting ensures quality, transparency, and successful projects.

5.6. Recommendations#

While the influx of funding from state and federal sources is welcome and more is needed, current federal and state funding levels are temporary, with a five-year closeout of most Bipartisan Infrastructure Law allocations and (likely) state budget shortfalls in coming years. As such, there is a continuing imperative to leverage those funds with private capital. Public funds may not last, may change focus, and are historically cyclical. Private investment strategies can complement public grant/loan funding to create composite portfolios of financial support for the accelerated implementation of landscape-scale restoration and mitigation projects. Despite this opportunity, private capital investment in forest and watershed restoration is negligible to non-existent in many regions. Yet, because private businesses are impacted by fire, drought, or other natural resource disasters, there is increasing recognition across the corporate and investment sectors that they can support forest and watershed health projects.

The following broad recommendations are offered:

Outcome metrics. One critical key to connecting the private sector is Creating clear, quantified metrics, feasibility studies, and a business case written in business language.

Funding portfolio. Prioritize and bundle projects to create funding economies of scale and specific project funding that match the multiple benefits of forest health and fire mitigation.

Blended finance. Take a blended finance approach to fund projects. The blended approach includes matching public grants with private funds and adding marketable forest product sales, carbon credits, and forecasted mitigation units created through thinning and prescribed fire projects enrolled in the future Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol. — Payors. Identify payors interested in avoided costs, e.g., Yuba Water Agency paying for forest treatments to reduce the negative impacts of wildfires on its water infrastructure.

Connect funders with implementers. Overcoming the challenge of connecting implementers with investors is a key challenge. This relationship-building challenge may be partially overcome with investment platforms, securing public funding, and creating better markets for wood products or looking to quantified ecosystem services markets such as carbon, biodiversity, and water.