1. Primer#

Understanding New Models for Accessing Private Investment

1.1. Background#

With the passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (better known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) in 2021 and the additional resources provided by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, there has been much attention on federal funding for the nation’s infrastructure. Water systems, including investments to improve drinking water health and security, wastewater and stormwater systems, and natural infrastructure, stand to benefit from this infusion of money. However, underneath this apparent largesse lurks a different truth—over 85% of all investments in our communities’ water infrastructure come from local sources—people like you and me paying our taxes and water bills to our local water utilities. Chronically underfunded, these utilities can benefit not just from infusions of public funds from Washington, DC, and state capitals but from smart, innovative financing strategies that leverage private investments to help public funding work harder.

A parallel news cycle highlighted the increasing appeal of environmental impact bonds and similar outcomes-based approaches to financing reduction in wildfire threats. In California, Blue Forest Conservation and the Yuba Water Agency launched a second Forest Resilience Bond in 2021, delivering 25 million (USD) to forest and watershed health projects in the Northern Sierra. Quantified Ventures launched a private land forestry initiative known as the Wildfire Mitigation Environmental Impact Fund, a revolving loan fund to reduce wildfire risk in Southwest Colorado.

What makes these approaches compelling? How do they work, and what benefits can they provide? This document hopes to clear up some of the mystery around these and other conservation financing strategies by:

Clearly describing collaborative project finance.

Unpacking the roles played by participants in these strategies and the structures that deliver private investment to projects.

Providing examples and lessons learned from existing finance collaborations.

1.2. Why Conservation Finance?#

Impact investment, outcomes-based finance packages, private-public partnerships, and other strategies to access private capital are, in some ways, variations on time-tested models, such as revolving loan funds, for accessing the capital needed to fund community projects and infrastructure. Many water utilities have traditionally issued bonds to borrow money to finance sewer systems, water treatment facilities, and other hard infrastructure. Debt-financing these investments has many advantages, including immediate access to the full amount of money needed for projects, reduced upfront costs compared to paying cash for projects, and inter-generational equity linking debt repayment to payors who benefit from its services across the project’s lifespan. In addition, debt financing may reduce the short-term financial impact on water ratepayers.

For example, the WaterNow Alliance points out that if a utility with a 70 million (USD) annual budget were considering investing 10 million (USD) in a major GSI incentive program, the utility would have to raise rates by 14% to pay for the program out of its annual operating budget. If, instead, the utility debt financed the program and paid for it over 20 years, less than a 1% rate increase would be needed to implement the same $10 million program (Caroline Koch, personal communication).

1.3. Benefits#

Although not widely used, the benefits of leveraging public funds with private are many:

Matches investment-ready capital with on-the-ground restoration projects that yield environmental and social returns.

Accelerates the pace and scale at which restoration and green infrastructure are funded and scaled. Many of the previous examples noted are infrastructure—and water-focused. However, integrating nature-based solutions to restore riparian, forested, farmland, and other habitats is critical to these efforts. Conservation finance can yield these dual benefits by raising funds upfront and decreasing the time for project completion from decades to 2-3 years.

Stabilizes otherwise irregular funding from public sources, allowing work to move forward more rapidly and predictably, significantly aiding cash-poor non-profits and municipalities in starting and completing projects. Grant and public loan programs typically reimburse utilities for incurred project costs. Private finance can reduce the financial challenges this creates for water utilities and their partners.

Builds local capacity and greatly eases the contracting burden across project proponents.

Can be structured to re-distribute the risk for project design and success away from the payor and toward the implementer (e.g., via a pay-for-performance approach).

Unlike traditional debt financing, non-traditional strategies to access private investment offer some advantages, particularly for smaller and mid-sized water agencies. First, many strategies can transfer risk from the water agency and public to private investors and investment facilitators. What do we mean by this? Initially, approaches such as the partnerships developed by Corvias Infrastructure Partners placed the responsibility for financing and delivering infrastructure projects in the private sector. Sometimes referred to as private-public partnerships or Design-Build-Finance-Operate-Transfer project delivery, this approach can reduce burdens on water agency staff and open finance opportunities when agencies lack the expertise and capacity to engage private investors directly.

Risk can also be transferred by linking repayment rates to the success of the project; in essence, a water agency is committing to pay for the benefits of a project rather than for the project itself. An interesting example is the Bailey’s Trail System Environmental Impact Bond, which delivers a mountain biking trail network to a rural community in Ohio. Repayment of this investment isn’t linked to the completion of the trails but to the expected increase in community economic activity in the local community. This economic uplift was the purpose of the project and financing.

Another benefit can come from using private investment to leverage multiple funding sources, creating a portfolio of funds that can repay the initial investment. The North Yuba Forest Resilience Bond is an excellent example of a debt-financed structure that combines private and public funds to accelerate and scale up watershed health projects. Private investment comes from insurance companies and foundations and avoided cost payments from Yuba Water agency as the payor.

Finally, private investment strategies may be accessible for green and natural infrastructure projects with limited access to federal and state funding and financing programs, such as State Revolving Loan Funds. Impact investment bonds have successfully delivered green stormwater infrastructure projects in Atlanta and the District of Columbia.

1.4. Private Investment in Action#

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to developing a locally relevant private finance strategy, but some key elements appear in many of the pioneering examples in this field. At a most basic level, private finance of water infrastructure requires relationships between stakeholders or beneficiaries who can participate in the planning and initiation of projects. These beneficiaries may also be project investors; however, investors may be an entirely separate set of entities.

Carbon & Ecosystem Service Markets

Carbon markets have become a major investment for climate change mitigation, helping fund many reforestation and forest conservation projects. Not without their critics or failures, investing and implementing carbon projects can be complicated to develop, implement, and track. Other new markets quantifying biodiversity and water are nascent but offer similar investment promises to protect natural resources and mitigate climate change.

AWE Protocol. Spatial Informatics Group and Element Markets developed a forecast methodology under the Climate Forward program to recognize the climate benefits associated with fuel treatment activities that lower the risk of catastrophic forest fires and their emissions. Known as the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Forecast Methodology, the Climate Action Reserve protocol could provide complementary funding for thinning and prescribed fire projects to grants and private investments. The Protocol differs from carbon offsets in that forecasted mitigation units (FMUs) are issued for forecasted greenhouse gas reductions or removals. FMUs are used to mitigate anticipated future emissions, such as wildfires.

Markets. Market prices for carbon credits vary depending on a given project’s size and location, treatment type, and the carbon market or registry used. Carbon credits can be realized for projects of any size and located on federal, state, and private lands. See the Avoided Wildfire Emissions Protocol section as another approach that is easier to implement than carbon sequestration credits or markets since the avoided costs are already calculated, and proponents do not have to seek an entity to purchase the credits. New markets, such as creating biodiversity credits, are starting to be discussed seriously, such as at COP16 in Colombia in 2024. These credits have a way to go before they are scientifically robust and practical for local communities and Indigenous peoples.

Embodied Carbon. Although it may be several years from implementation, developing and marketing low-carbon building materials is another new opportunity. Buildings are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, so building decarbonization is becoming a priority. For example, Washington, Minnesota, California, and New York states all passed legislation in 2024 to reduce building greenhouse gas emissions. Embodied carbon is the lifecycle of greenhouse gas emissions from creating, transporting, and disposing building materials (Carbon Leadership Forum, 2022). In other words, embodied carbon is any building’s carbon footprint contained in its building materials. It differs from operational carbon, produced by a building’s energy, heat, and lighting. The California Air Resources Board is developing a comprehensive strategy for embodied carbon and is seeking comments following the signing of ABs 2446 and 43 (CARB, 2024).

Ultimately, the central role is played by the agency or agencies who are the primary payors for the project. These agency payors are responsible for repaying all debt, including any interest on borrowed money. Payors may be able to draw upon rate or tax revenues and other sources of income to repay the investors. In the water sector, payors may be motivated by the need to comply with regulations or other legal mandates, the obsolescence of outdated infrastructure, or the need to respond to emerging conditions or threats. For community groups or other non-agency proponents of a project, establishing a partnership with a payor is instrumental to the success of most financed projects.

Let’s take these roles in turn:

Collaboratives. Often, successfully planned, financed, and implemented projects succeed because they are informed and supported by a collaboration of affected beneficiaries or stakeholders. These individuals and organizations can ground a project in the surrounding community’s needs, contribute expertise and perspectives that inform project design and implementation, and contribute social capital that leads to political support for the project. This support can translate into opened opportunities for funding, investment, and other forms of support.

Investors. Federal or state agencies may contribute partial funding for a project or provide various financing support such as credit guarantees, credit enhancement or loss reserves, or technical assistance. Investors can come from many sectors. For instance, insurance companies, retirement funds, university endowments, and institutional investors may offer below-market interest rates if a project meets its environmental or social benefit goals. Individual impact investors, acting alone or through composite funds, may be willing to provide capital at reduced rates of return to environmentally or socially beneficial projects. Finally, philanthropic foundations may be available to invest in projects that fulfill their programmatic interests. One benefit of private finance strategies is the potential to blend multiple investment sources into one project portfolio, perhaps even sequencing these sources of financing to discrete phases of a project.

Payors. Ultimately, investors must be repaid for the financing they provide. This repayment obligation will often fall on a public water agency or other governmental body with an operational or ownership interest in the proposed project. Agencies with a regulatory or other driver that compels their interest in the benefits of a project will be the most ‘secure’ payors. However, other forces may motivate agencies, institutions, and even businesses to pay for (or contribute toward) the outcomes associated with a successful project. Corporations with sustainability, resilience, or environmental justice commitments are equally driven to invest in projects that provide beneficial outcomes. Economic development agencies and entities may have funding to contribute to projects that meet local job creation or business engagement goals.

Combining these actors into a financing package keyed to a natural infrastructure project may be less straightforward than the pathway to traditional bond issuance and is certainly more complicated than simple cash pay-go approaches to capital improvements. Where simpler approaches to investing in infrastructure are available, it’s likely best for an agency to pursue those avenues. However, private finance can unstick projects long deferred in waiting for traditional finance opportunities or capital improvement budgets to provide enough cash. Private finance can also deliver projects that are larger in scale and have beneficial outcomes than can be supported with annual grants or budget cycles. It can be useful to look at the financing structures adopted by existing private investment models to understand better the interplay between investors, payors, and beneficiaries.

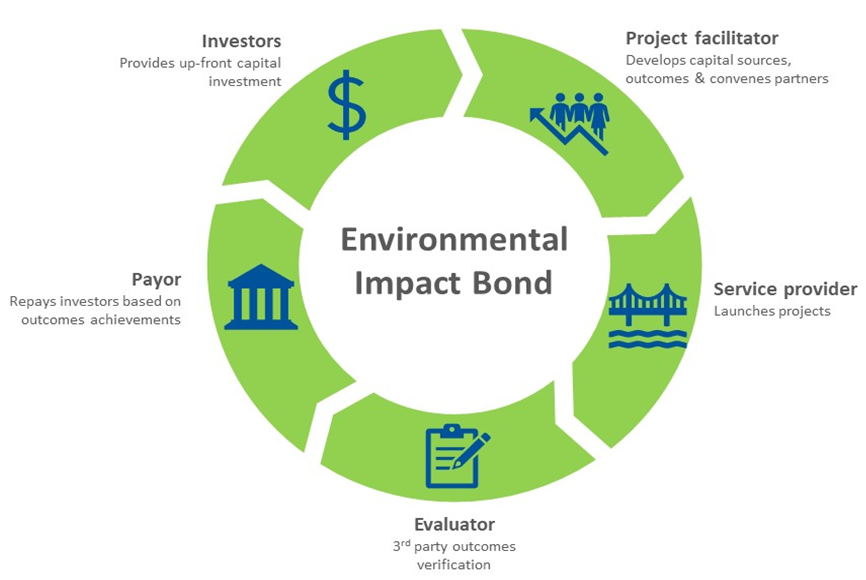

In 2017, Quantified Ventures and the District of Columbia’s Department of Water and Sewer (DC Water) launched the nation’s first environmental impact bond focused on implementing green infrastructure to reduce sewage overflows and flooding [Martin and Applebaum, 2021]. This outcomes-based investment package tied the rate investors earned to achieving specified environmental performance goals. The investment package structure linked DC Water to private bond buyers (Fig. 1.1). The structure used by Quantified Ventures, DC Water, and their investors follows the track illustrated below. The role of the third-party evaluator is noteworthy in this outcomes-based repayment scheme. Five years after launching the project, the evaluator confirmed that stormwater runoff had been reduced by nearly 20%, a level that met the bond’s base-level repayment criteria [Lindsay et al., 2021].

Fig. 1.1 Quantified Ventures environmental impact finance bond.#

Blue Forest’s Forest Resilience Bond adopts a somewhat different approach (Fig. 1.2). The Bond, more of a revolving loan instrument, is not strictly an outcomes-based financing strategy. The project payor, Yuba Water Agency, makes payments to investors unrelated to achieving the project’s many benefits. The structure adopted by Blue Forest enables the creation of a portfolio of investors and funders who repay and complement the Agency’s funding.

Fig. 1.2 Forest resilience bond entities. Blue=investment flows, green=return, red=agreement (adapted from Blue Forest).#

Investors, such as Calvert Impact Capital and AAA Insurance, provide up-front capital by paying into the Forest Resilience Bond (Fig. 1.2). This aggregate fund, administered by the National Forest Foundation, pays contractors and local NGOs to plan and deliver forest and watershed restoration activities. Once completed, Yuba Water Agency (the beneficiary) repays implementation costs to the fund, which repays the investors.

1.5. Additional Cases#

In addition to the three examples mentioned above, other examples from innovative private financing showcase the flexibility and appeal of these strategies.

Corvias

Corvias, a leading developer of private-public partnerships, built on its success in Prince George’s County, Maryland, with the Fresh Coast Protection Program launch with the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District. Through this program, the partnership secured $75 million in financing, providing resources enabling Corvias to design and construct green infrastructure projects to help MMSD meet its regulatory goals. The outcomes-based partnership commits the District to pay a fixed cost per gallon to Corvias, with the ultimate target of installing 8.45 million gallons of stormwater retention capacity.

EIFDs

Several municipalities in California pioneered Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts to leverage the value of infrastructure improvements as collateral for obtaining the resources to implement these projects. Using tax increment financing, this approach allows water agencies and municipal governments to issue bond debt for projects that future increases in property tax revenue will repay.

1.6. Parting thoughts#

These examples show the possibilities and benefits of creative strategies that bring private capital to support water infrastructure projects [Odefey and Russell, 2020]. However, some challenges to securing private finance have stymied broader acceptance of this approach–and more effort is needed to understand and reduce the impact of these obstacles. Some of the costs and challenges will be familiar to public utilities: lack of familiarity and capacity, uncertainty about how to measure outcomes best, or lack of established networks between utilities and investors. See Chapter 5 for a more in-depth discussion of these barriers to increased uptake and scaling of collaborative finance.